Why is Honduras so Violent?

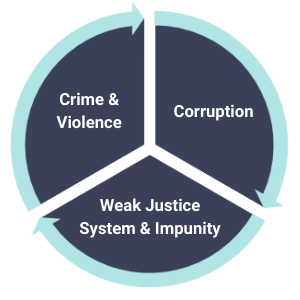

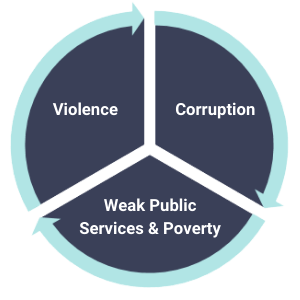

Honduras has been known as one of the most violent countries in the world. To understand violence in Honduras, you have to understand one negative, recurring cycle.

Organized criminal groups like gangs and drug traffickers pay off police, prosecutors, and judges to get away with their crimes. This corrupts the criminal justice system. Without a functioning justice system, impunity runs rampant for criminals and murderers: they are rarely held accountable for their actions. This, of course, leads to more violence and crime.

While factors like gang violence, drug trafficking, impunity, poverty, and corruption have made Honduras violent, the country has made remarkable strides in working towards peace. Honduras was previously the most violent country in the world, but its violence rates have dropped in half in the past decade. Learn more about the factors contributing to violence in Honduras and how Honduras can become more peaceful.

Gang Violence

Sources differ, but it’s estimated there are as many as 40,000 active gang members in the country.

Gangs play a key role in the high rates of violence in the country. In a context of poverty and limited government services (like education and health), gangs are likely to form. In Honduras’ marginalized urban neighborhoods, gangs provide an opportunity for young people to find identity and a source of income.

Both MS-13 and the 18th Street gangs are present in Honduras, and it’s estimated that there are up to 40,000 members in Honduras. Gangs commit many different crimes, including extortion, street-level drug peddling, robbery, and murder-for-hire schemes. Violence at the hands of gangs can result for various reasons:

- If extorted businesses do not pay “war taxes” (payments demanded by the gangs), gang members may kill them.

- If multiple gangs want to sell drugs in the same area, they may fight over that territory.

- Gangs have strict codes for their members that, if broken, are punishable by death.

Drug Trafficking

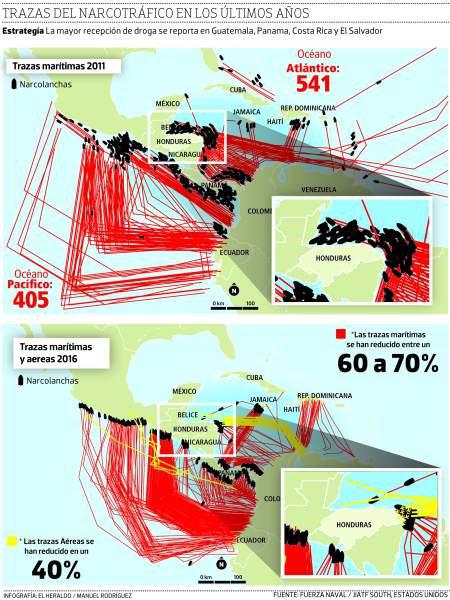

The U.S. government estimates that approximately 4% of all cocaine shipments from South America passed through Honduras by air or sea in 2019 of cocaine, equivalent to a U.S. street value of over $11.5 billion at current rates.

Honduras has the misfortune of being situated between South American cocaine production and U.S. drug consumption. Because of Honduras’ impunity and weak political system, drug traffickers saw an easy path to the market in the U.S.

Most drugs come to Honduras by boat through the Gulf of Fonseca (shown in red in the map), while other drug shipments come by plane to the marshy east coastline (shown in yellow in the map). As these maps show, there has been a significant shift away from using Honduras’ Caribbean coast as a stopping point for drug trafficking. However, around 120 metric tons of cocaine still pass through the country every year.

Competition between drug traffickers often results in violence. Traffickers often avoid detection by paying off authorities, weakening the justice system. The National Police have historically been implicit in drug and arms trafficking through the country, receiving bribes in exchange for turning a blind eye or cooperating with traffickers moving cocaine north. In addition to police officers, the drug trade has corrupted mayors and members of Congress, and the current president’s brother is awaiting sentencing for drug trafficking in the U.S. Crime, and the money that comes along with it, have contributed to the deterioration of the justice system.

Impunity

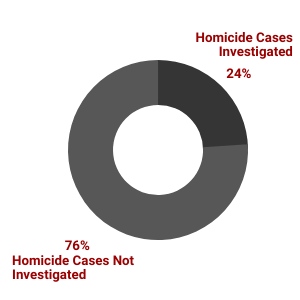

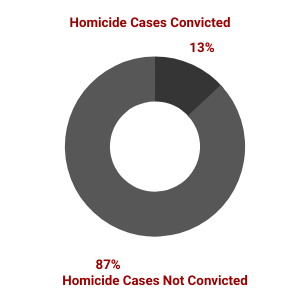

Only 24% of homicide cases are investigated, while only 13% reach a conviction.

Violence and crime in Honduras are likely to go unpunished for a number of reasons. Historically, Honduras has had a weak police force. Criminal investigation is severely hampered by limited funding, a lack of high-tech investigative tools, corrupt officers, and poor police education.

Even when the police are able to do their jobs, the judicial system is overwhelmed, with a backlog of over 180,000 cases due to inefficient processes and a lack of resources. The weaknesses in the police and judicial system mean that many cases are left in impunity: 76% of homicide cases are not investigated, and 87% of cases never reach any sort of judicial resolution. This rate of impunity means that people aren’t held accountable for their crimes, leading to flourishing criminal activity.

Corruption

Honduras received a score of 24/100 in the Corruption Perceptions Index, where 0 is very corrupt and 100 is very transparent.

In Honduras, government institutions are weak, often failing to provide basic public services such as education and health care. Corruption in the police and judicial systems make victims afraid or unwilling to report crimes. And weak or corrupt institutions fail to protect individuals such as journalists, civil society members, legal professionals, and human rights defenders such as Berta Caceres.

Corruption is not limited to the justice system, of course. Cycles of impunity and crime occur with gangs and drug traffickers, but they also occur with government employees and businesspeople. Some government employees and allies in the private sector have devised a number of devious ways to skim money off the top of budgets from government institutions such as the Ministries of Health or Education.

The most famous of these cases is the embezzlement and bribery scheme in the Honduran Institute of Social Security, a health insurance program and system that makes up about a third of the government’s overall public health system that came to light in 2015. Some estimate that over $300 million were stolen by government employees in this case.

Corruption weakens important public services – like schools and health clinics – which could make a difference in alleviating social problems in crime-ridden communities. This contributes to an environment in which violence and crime can flourish, and public services are riddled with corruption.

Poverty

About 48% of the population lived in poverty, with as many as 60% in rural areas.

There is another cycle that helps explain violence in Honduras: poverty. Poverty provides a context in which high levels of violence and crime can flourish. A lack of jobs or other economic opportunities push some – especially young men – toward crime or gangs to improve their financial prospects. The violence creates obstacles to economic activity (like extortion) that in turn create instability and insecurity. The poor rely on public systems for services like health and education, but corruption prevents them from receiving a quality education or getting the health care they need.

Gary Haugen, in his book The Locust Effect, compellingly argues that this cycle is not being addressed by NGOs, governments, and multilateral organizations around the world. He says: “Efforts to end global poverty and to secure the most basic human rights for the poor are failing because crime and violence against the poor are not being addressed.”

While the outlook on poverty and violence is on a positive trajectory, there is still much work left to do: 48% of the population is living in poverty. Further, Honduras has the second smallest middle class in Latin America at only 10.9% of the population. A larger middle class is associated with lower levels of violence, stronger public institutions, stronger economic growth, and greater societal stability. Working to stem both violence and increase economic opportunities is integral to sustainable development.

How ASJ is Responding

While the cycle of violence, corruption, and weak systems has created deep challenges for Honduras, this cycle can be broken. Over the past 10 years, violence in Honduras has been cut in half, and ASJ’s interventions have led to a 75% reduction in some of Honduras’ most violent neighborhoods. Cases of corruption and drug trafficking are coming to light and being brought to trial. Communities that were once lawlessly ruled by gangs now have reliable law enforcement standing up for justice. Criminals are being held accountable for their crimes, and more people have access to justice.

We have seen that

peace is possible for Honduras. At ASJ, our work in Honduras focuses on securing justice for the vulnerable and making government systems work for all members of society. We do this through both community-level interventions and national reforms. This video tells the story of our homicide investigation program, which has created peace in one of Honduras’ most violent communities.

Learn more about ASJ’s response to corruption, violence, and poverty in Honduras, and our pursuit of a more just society.

Updated April 2020