“Widespread corruption, impunity, negligence, and tolerance”: this was the state of Honduras’ police force, the Police Purging Commission reported in their first quarterly presentation to the Honduran Congress.

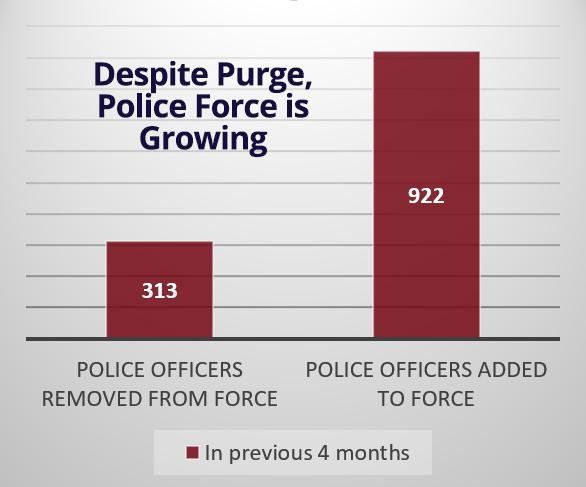

The report covered the work of the Commission over their first four months, in which they confronted threats and personal attacks in order to evaluate the police force from the top, down – evaluating 946 officers and removing 313. Just 297 mid-ranking officers remain to be evaluated, then the commission will move on to the daunting task of evaluating the 10,000 entry-level officers.

The members of the Police Purging Commission – including ASJ’s (formerly known as AJS) Omar Rivera and Pastor Alberto Solórzano, who sits on ASJ-Honduras’ board – have a bigger vision for the police than just removing corrupt officers. They see this as a rare chance to create a better-organized, more-transparent, and more-trustworthy force.

In their evaluation of the police force, the Commission found disorganization, corruption, and a culture of covering up each other’s crimes. Active-duty police officers had uninvestigated links to gangs, drug traffickers, or organized crime. Others with open judicial cases of robbery, extortion, sexual abuse, or domestic violence continued to be promoted up the ranks.

“All these situations mentioned are not new,” the Commission stated in their report to Congress. “For years it has been known that corruption invaded the police body – for years the situation in the National Police has been public – and no one has done anything.”

After years of impunity, the Commission is now ensuring that this systemic problem will finally be addressed. With special care to follow labor laws and due process, police officers with known or suspected links to crime are being removed from the force, and their documents sent to the courts for investigation.

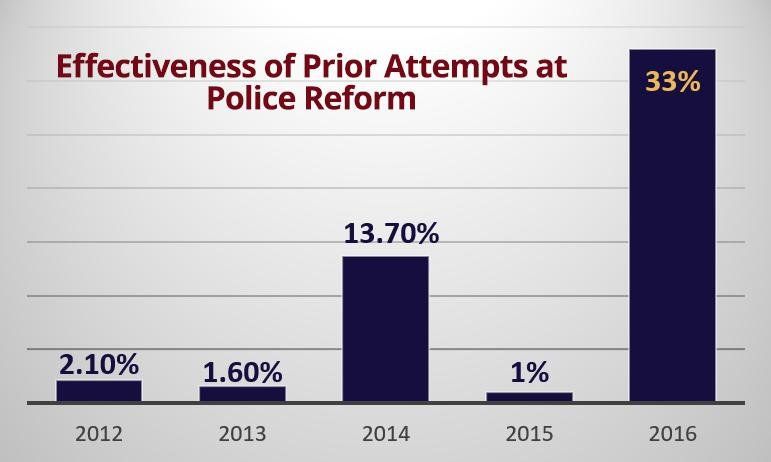

With no budget, the current Commission has fired a greater percentage of evaluated officers than any other attempt – and unlike past attempts, they have all been high-ranking officials.

The Commission already has specific and detailed proposals for addressing the root problems. In addition to evaluating the officers themselves, they are also looking closely at job descriptions and positions within the force. The evaluation highlighted positions that are vague, duplicated, or poorly specified. The Commission’s proposals will create a new structure of functional positions in which officers will have clearly defined duties, responsibilities, and fit within clear hierarchies.

As a result of years of advocacy from ASJ, police training has also been revamped, extended from a few months to a full year of courses and training focused more on human rights and community policing. The first graduating class has entered the force just a few months ago and shows promise for Honduras’ future police.

In the coming years, the police force will be strengthened not just in policy but also in numbers. Currently, Honduras has fewer than half of the police officers the United Nations recommends. A plan proposed by the Secretary of Security would nearly double the police force within the next six years, all new officers having been screened, hired, and trained in the more transparent and effective protocols suggested by the Commission.

“The special commission’s track record so far suggests that the Honduran government is taking this iteration of police reform seriously,” the journal Insight Crime reported.

“If the effort ultimately proves successful, it could provide a model for other countries in the region seeking to improve their public safety institutions.”

It’s a process that the Commission is fully committed to. “No threat will prevent the transformation of the National Police,” said Omar Rivera. “Nor will any threat diminish our enthusiasm to achieve the institution and offer it to society.”