“We already have the hitmen, right?” one Honduran police officer said to another, unaware that the security camera in the room was recording him and that, years later, these words would come back to haunt him.

“Yeah, we have them,”

the second officer responded, “we have four with vehicles.”

The officers in the room began to discuss the daily habits of their target – the anti-drug czar, who had been outspoken about corruption in the National Police force.

“Aristides González always walks alone, he passes by here every day.”

“Hey,” another officer asked, “has the boss sent us the money?”

According to a leaked video transcript published this April by a Honduran newspaper, leaders of Honduras’ national police force gathered together in 2009 to plan the murder of Aristides González, paid by a known drug trafficker.

Just a few days after hearing the revelations, the Honduran Congress had passed an emergency declaration to “purge and transform” the police force, calling for a three-member Commission to oversee the removal of corrupt officers. The President immediately signed it into law and appointed the members – Vilma Morales, a former president of the Supreme Court, Alberto Solórzano, a pastor and president of the Honduran Fellowship of Evangelical churches as well as an ASJ-Honduras board member, and finally Omar Rivera, who through ASJ (formerly known as AJS) and the coalition Alliance for Peace and Justice, has been among the loudest voices calling for police reform.

“This is the time for change,” Omar told journalists. “It’s now or never. All sectors are in tune. We cannot fail and we cannot fail Honduras.”

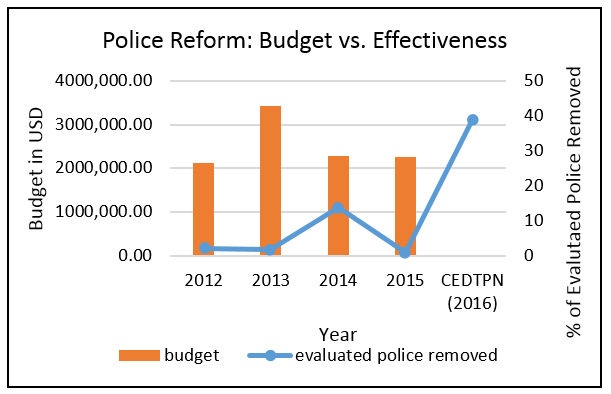

This “purge” is not a new concept. Between 2012 and 2016, Honduras had tried three different times to clean up the force, spending over $10 million, and firing only a handful of low-ranking officers. Fear of officers’ connections to politicians or organized crime meant the most corrupt were left untouched.

The three-member commission, called the “Special Commission for the Purging and Transformation of the National Police”, immediately took a different approach, starting from the Police Generals – the highest-ranking officers – and working their way down.

“We have done in two months what has never been done before” – Omar Rivera

Within a few days, they had reviewed the files of the Generals, consulted human resources and the Judiciary, and made their decision – they would recommend the suspension or firing of five of the nine officers.

Over the next few weeks, the Commission continued with their close scrutiny, in 50 days reviewing the top 272 officers in the force and removing 106 of them. This work, naturally, earned them enemies. One commissioner’s family was trailed for miles in an unmarked vehicle; another woke to a death threat slipped underneath his door.

But the Commission’s work is dangerous and requires national and international support. Powerful people such as those who called for and executed the assassination of Aristides González are continuing to act. Because of this, we have begun a prayer and advocacy campaign asking for protection and support for the Commission in the face of these threats.

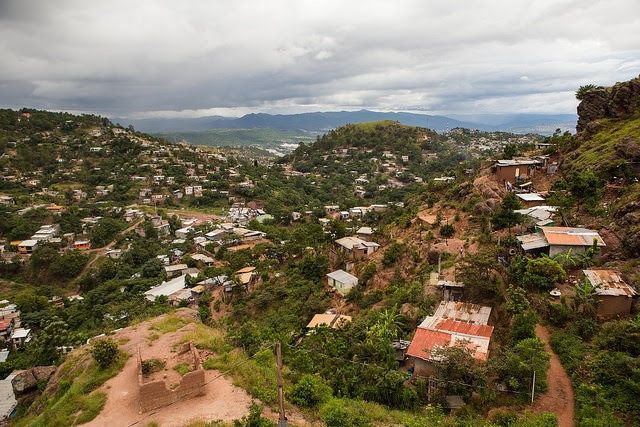

Honduras has spent years with sky-high homicide, corruption, and impunity rates. But the trends are beginning to turn. Corruption perceptions have dropped, homicides have been reduced for the third year in a row, and Honduras is no longer the most violent country in the world. Bold initiatives such as the police purging process offer hope for a different future, one where citizens trust the police, where criminals face justice, and where all can live in peace.