January 1, 2017

This story was originally published in Spanish by ASJ online magazine Revistazo on September 8, 2016. It details ASJ's (formerly known as AJS) involvement in investigating the murder of a young girl. Content warning: language, descriptions of physical and sexual assault.

Chapter 1: Where are you taking me?

Thursday June 26, 2014 12:40pm

The heat is intense here in the Sinai neighborhood, in the sector of San Pedro Sula called Rivera Hernández, in northern Honduras. Andrea Abigail Argeñal Hernandez leaves the gates of the Carlos Alberto Hernandez Ramos School and lifts her hand to protect herself from the scorching sun, her small eyes squinting even more in the bright light. The 13-year-old smiles, as she usually does. Her clear skin and black curly hair make a nice contrast against her orange shirt, blue jeans, and white sandals, a recent gift from her mother.

Her cousins Jefferson José and Skarlet Michell have already given her a kiss on the cheek and left for their classrooms. Her aunt, who lives close, had woken up sick and asked Andrea to do her a favor and walk her cousins to school. Abigail starts to walk the block and a half between the school and her house, wondering what she will do with her free time until she returns for her cousins in the afternoon.

She doesn’t notice two skinny boys with hard eyes standing to the side of the small black gate of the school. But after only three steps they grab her.

Startled, she shouts.

She turns her head and, when she sees who they are, is filled with fear.

They don’t look like thugs. “El Pelón” (Baldy) is 21 years old, short, and so thin he almost looks malnourished, with a long face and hair cut short. “Pacheco” is similar, 20 years old, of medium height, with slanted eyes and normal hair: they say he even shaves his eyebrows.

But Andrea, like everyone who lives in the Sinai, Cerrito Lindo and Central neighborhoods, knows too well who these two are: members of the frightening criminal gang, “los Ponce,” responsible for countless rapes, assaults, extortions, and murders.

Andrea’s mind goes into shock. Three weeks ago these boys had threatened her. Nothing good awaits her.

“What’s wrong with you?” implores Andrea Abigail.

“Walk, you bitch,” one of them responds.

“Where are you taking me?” the girl shouts, trying to catch the attention of the people walking up and down the street. There are dozens of parents walking, holding their children’s hands to take them to school. But no one turns to look. If a child starts to turn curiously, their father or mother pulls their hand and hisses, “look away”. In Rivera Hernandez, everyone is threatened, afraid of their own shadow. The criminals – who form a half dozen criminal gangs – are everywhere, and there are those who say that even in the police, there are agents and officials related to these groups.

No one wants to end up dead for having seen something they shouldn’t have.

“You already know. We warned you that we didn’t want to see you here, now we’re going to break you,” says one of Andrea Abigail’s captors.

“No! Please don’t hurt me!” the young girl begs, her voice racked by sobs.

They take her, almost dragging her through the dusty street, to a small car that waits a block and a half from the school.

They force her to climb in, the car starts up, and speeds away towards the South and the neighborhood Planeta.

Chapter 2: Days of Anguish

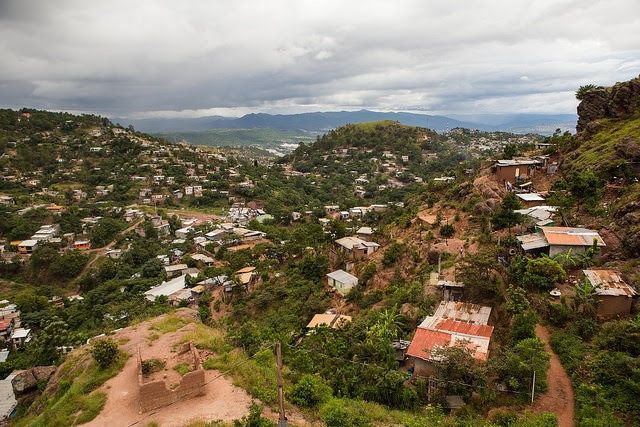

Andrea Abigail was born the second of three children in a hardworking family from the neighborhood Cerrito Lindo, a community as poor and violent as the rest of the neighborhoods that that make up the region of Rivera Hernandez. Rivera Hernandez is made up of 39 neighborhoods in southeast San Pedro Sula, the “industry capital” of Honduras. Andrea Abigail and her family lived in the second street of the Cerrito Lindo neighborhood, almost on top of the border between that and the Sinai neighborhood, a half-block from the school where her cousins attended. A few blocks away is also the Rivera Hernandez police post.

Andrea’s father, Emerson Berthony Argeñal, is a construction worker who earns an honest living, and her mother, Karen Suyapa Martinez, is a housewife. At thirteen, Andrea was usually happy, like any teenager who hopes to make the most of the changes that come in the prime of her life. She was at the age of making friends and of meeting your first love. She was in 8th grade at the Copantl Institute, and punctuated her studies with laughter and jokes with her friends and classmates.

Thursday June 26, 2014 5:40pm

Five hours have passed since they took Andrea, and no one from her family knows. Karen Martinez, Andrea Abigail’s mother, is asleep. She had spent the morning running errands in San Pedro Sula’s downtown; the intense heat caused a strong headache and so she went to bed. Suddenly, the shouts and laughter of her nephews, Jefferson and Skarlet, who appear in the door to visit her having left their classes, wake her up.

“Abigail,” says Karen from her bed, massaging her temples from the pain “Bring me a glass of water to take a pill, please”.

“Aunty, Andrea isn’t here,” says Skarlet from the living room.”

“What did she do?”

“I don’t know. We came alone because she never came to pick us up,” replies the girl.

Fear seizes Karen. Immediately she recalls an incident that happened three weeks prior, when Andrea Abigail came home crying because of death threats she received from two heavily armed men who stopped her outside her school moments after she left class.

They warned the girl that they didn’t want to see her there, and that they would kill her.

Since that day, she had stopped going to school.

Without thinking twice, Karen throws herself out of bed and begins an unsuccessful search for her daughter. She visits several relatives who live in the area but none of them know the whereabouts of Andrea Abigail. She goes to the school, but finds it closed. Every few minutes, she calls her daughter’s cell phone but it’s turned off. Time flies. Now night, Ms. Karen walks desperately from street to street throughout the community without hearing any information about her daughter.

9:30pm

Karen is tired, and feels she could die from anguish. She does not know what to do. She returns to the house where her husband, Emerson, has just come home from work. She can’t keep herself from crying. She tells everything to her husband who only now realizes that his daughter has disappeared. Emerson cries and hugs her. After a minute they wipe their eyes.

“Well, we have to make the report,” says Emerson.

* * *

“Good evening,” say Emerson and Karen as they enter the station of the Rivera Hernandez Preventative Police.

“How can we help you?” answers the police agent on watch that night.

The parents explain that their daughter has been missing for several hours and that they haven’t heard anything from her. The station of these officials dedicated to “Serve and Protect” is located just a few meters from the place where they had taken girl, but the police know nothing about it.

“Did you already look for her well?” asks the police.

“Yes, we already went to several places and no one gave us any information” – answer the parents.

But the police officer, bound by the law to prevent the difficult situations of the neighbors in the community, laughs sarcastically, and instead of assisting the concerned parents, says:

“Ah, people come here every day to make reports, and then they come back saying that the girls had run off with their boyfriends. She must be with her boyfriend,” he insists.

Andrea Abigail’s distraught parents see the attitude of this agent and grow even more worried. Feeling helpless, they burst into tears.

Uncomfortable with their tears, the officer insists – “don’t worry, she’s surely safe and you here suffering.” He takes a few notes and asks them to come back the next day.

“I’ll let you know if something comes up,” he says.

11:30pm

Already almost midnight, Andrea Abigail’s parents arrive at the First Station, the primary office of the National Police in San Pedro Sula. If the officers at the local station didn’t take them seriously, maybe the ones here would.

The officers take the report, but they do nothing either to recover the girl.

Emerson and Karen return home despairingly, filled with concern, and lay down to toss and turn, toss and turn, unable to sleep.

June 26 – July 4, 2014

In the days after the disappearance, with the hope of finding their daughter alive, Andrea Abigail’s parents print out photos to show people when they ask if anyone has seen her.

They cover the entire area, street by street, stopping and questing everyone they find.

“Sir, by any chance have you seen this girl…?”

“Ma’am, is there any chance..?”

“Young man, have you…?”

But no one gives them the response they are looking for.

“I was going around looking by my own means, but I didn’t find any information,” the inconsolable mother remembers, afterwards.

“People told us, ‘I heard shouts over there,’ others said they had heard them in a different place, but we alone couldn’t go there. Others said she could be buried and gave us directions to the house,” – recounts Emerson, sorrowfully.

Finally, they found someone who gave them a clue about the terrible truth, but just a clue.

“Some 20-year-old pale guy took the girl, they call him Pacheco,” one of the neighbors told Emerson and Karen.

“For a while now, he’s been wanting that girl, see, he would always watch her when she came out of the school and would say to the others, “That girl’s really fine, I’m going to have her,” the neighbor said.

Now, Emerson remembers, “We asked for help from the police and they said that they needed to talk with him about what he had told us, but we never told them, they didn’t help us and we continued to look for the girl until Saturday, July 5 when my wife Karen received the call…”

Saturday July 5, 2014 7:00pm

Karen, Andrea Abigail’s mother, rests in the living room of their house. Sitting on the sofa, she gazes at a picture of her daughter saved on her phone. All that day and the previous nine have been an intense search for her daughter but without results. She feels anxious and weighed-down by the uncertainty. No one has given real answers about the disappearance of her daughter, only speculation. Her mind can’t stop racing, while from her eyes flow rivers of tears.

Suddenly her phone rings and her display changes from the smiling image of Andrea Abigail to that of an unknown number: 9946-2836.

Karen answers but the call had already been ended. Her heart beats faster. Could it be someone who has information about her beloved Abigail?

She returns the call. On the other side she only hears noise.

It cuts out and she calls again. Again, she only hears noise.

On the third time someone answers her. A young male voice says:

“Stop fucking around. She’s buried in Melvin’s house.”

Chapter 3: There are many criminals here

The Rivera Hernandez sector is an urban settlement established in the 1970s by families displaced by Hurricane Fifi. Since the beginning, the area has been marked by violence. Today, the 150,000 inhabitants of the area confront daily the challenges that come with living in a place where half a dozen gangs fight for territory.

Rivera Hernandez is filled with gangs and criminal groups, the majority teenagers with low levels of schooling and a lot of energy to carry out any “little job”, as difficult as it may be.

Many who live in the area believe that the police officers assigned to the Rivera Hernández station keep close links with gang members and members of other criminal gangs. The lack of trust in the authorities has provoked in the population a custom of living terrified by the blood and fire of guns.

In November 2014, Revistazo published that the criminal operations of six criminal gangs resulted in the displacement of many families who had to abandon their homes in order to save their lives. The desolation is immediately apparent; upon entering the sector you can see how houses in ruins, their roofs, windows and doors ripped off by the thugs that claimed them. The situation is also compounded by commercial buildings that suffered the same fate.

The author of this report, after traveling through the area, finds himself with a local neighbor and asks about their life here.

“Look, I’ll tell you, but come over here a little bit,” he said.

He moves behind a concrete wall, as if to prevent someone seeing him talking with a stranger, and in a low voice says:

“Here, there are many criminals, in all of the Rivera – shoot, already in the afternoon you can’t walk confidently because even the police are paid off,” he said, talking in secret.

In recent years one of the most feared gangs in the Rivera Hernandez were “los Ponce”.

This was a criminal gang made up of drop-outs from the Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13 gang, and created by Cristian Ponce, who was born and raised in the area. They say that Cristian wanted to be chief of the MS but couldn’t, so he formed his own criminal group decided to operate in the communities of Sinai, Cerrito Lindo and the Central. He marked his territory and competed with five other criminal organizations: The Olanchanos (“From Olancho”), The Tercerenos (“13s”), Pandilla 18 (“18 Gang”), Los Vatos Locos (“Crazy Guys”) and the MS-13 all with representation in various points of the Rivera Hernandez area and competing openly with actions of contract killings, selling drugs, extortion, theft of vehicles and arms trafficking among other crimes.

Among the most notorious members of the Ponce, almost all are young people under the age of 25: Víctor Manuel Pavón, alias “El Pelón”; Luis Gerardo Fuentes, alias “Kevin Pacheco”; Moisés Ramírez Castellanos, alias “The Moisa”; Ronald Chávez, alias “Little Roland”; Samuel Jorlin Salazar, alias “The Barber”; Javier, alias “The Longe”; Jonatán Cecilio Sánchez Hernández, alias “Cleaford”; and Roller Miguel.

The group is involved in a long list of crimes. “Pacheco” is accused of killing Jorge Alberto Gevara Amador on June 9, 2014 in the Sinai neighborhood. “Cleaford” is accused of the murder of Sandy Marisol Rios Zabala, in April of 2014. Even the mother of “Baldy”, Claudia Patricia Prieto, was arrested on July 8, 2014 for illegal possession of weapons because they found a Armscor 30 caliber revolver buried in her yard along with a Noringo 9 mm caliber and a 9 millimeter Smith & Wesson gun, all used by the Ponce to commit their misdeeds.

The mother of “Baldy,” Claudia Patricia Prieto, was arrested for illegal possession of weapons found in her yard, all used by the Ponce to commit their misdeeds.

In the community there are those who say that Cristian Ponce and the Moisa worked really closely with the preventative police of the area.

Perhaps one of the most notorious acts of the Ponce gang – at least before the kidnapping of Andrea Abigail – was the murder of Melvin Ely Carnation Escobar in March of 2013 by “Baldy” and “Cleaford”.

Melvin, like Cristian Ponce, was born and grew up in the Sinai area. He was a neighbor and knew Cristian Ponce. During several years of hard work as a fisherman, he managed to save a good amount of money and invested in a grocery shop. The Ponce gang wanted Melvin’s money. When Melvin refused to pay the required “war tax”, the Ponce shot him three times in the head. Melvin’s family moved away, and the house was abandoned, the gangsters looted his shop and took over his house, which soon became a “casa loca” (crazy house): a home abandoned by their owners, used by gang members for the implementation of crimes, ranging from rape to murder and dismemberment.

It was in this house, Melvin’s house converted into a “casa loca”, that they buried Andrea Abigail.

Chapter 4: Two burials and one exhumation

Monday July 7, 2014, 11:15am

It has been eleven days since Abigail disappeared and her parents filed the complaint, and two days since they received a call saying their daughter was dead and buried in the yard of a neighboring house. No one has helped them. They realized later that Abigail was alive for at least a week in the hands of her kidnappers, who tortured and likely raped her. She could have been rescued if the neighbors who heard her screams had overcome their fear. She could have been rescued if the authorities had acted with diligence.

But it was not so. her parents, Emerson and Karen, were asked to bring the person who had given them evidence as to the potential whereabouts of the girl into the police station, but they could not do so. The informant was too afraid. The National Directorate of Criminal Investigation (DNIC) argued that they had no vehicle or researchers available to investigate.

Abigail’s parents

Today, in the Prosecutor’s office, they argue again with the desperate parents over the need for a report from the criminal investigations office.

Just steps away, a private investigator, who for the sake of this story will be known as “Ramón Rivera”, notices this man and woman in the Prosecutor’s office crying out for help to find their young daughter.

With his notebook tucked under his arm, Ramón approaches, observing them closely. After greeting the couple, Ramon earns their trust before asking them about their case.

The sobs from Abigail’s mother are uncontainable, but with great effort, she and her husband recount the details of their situation. Sharing their experience is a difficult thing to do, though their story has almost become a norm in a country that is considered to be among the most dangerous nations not at war.

The investigator, dressed in a blue long-sleeved shirt, beige trousers and almost-spotless black shoes, takes down every detail of the case in his notebook with his black pen. Five minutes later, Abigail’s parents seem calmer than they were when they started the conversation. At that point Ramón explains that he works for a human rights organization, and he is ready to help them.

After hearing about the house where they have heard Andrea Abigail is buried, Ramón asks them, “Do you want to go?”Their eyes, aching from tears and lack of sleep, light up, and for the first time in almost two weeks, they shine with hope.

“Blessed be to God who placed him in our path,” says the woman realizing that at last she is on the brink of finding out the truth

The three agree on a time and place, and an hour later, they meet.

They arrive at Melvin’s house, closed-up and abandoned since its owner was shot to death in March of 2013. The gate is open, and Ramón and Emerson, the girl’s father, cautiously walk into a huge courtyard filled with weeds.

Melvin’s House

The brush is over a meter and half high, but just a few steps inside of black metal gate, they see a white sandal. Emerson takes a photo with his cell phone and sends it to his wife Karen, who stayed behind.

“She was very upset because the girl was wearing those when she left the house,” the father of the girl recalled, in his statement for the judicial record.

Breaking through the brush with their feet, Emerson and Ramon arrive in the backyard of the immense house built on a 650 square meter property. In the middle of the brush, they notice a lump of loose soil covered with debris from freshly cut weeds. Close by are two pieces of wood. They pick up the wood and begin to dig. The earth is loose and easy to move. A meter down they discovered the body.

A meter down they discovered the body

“We saw a person’s leg, covered it up and decided to go to the police investigation office and do the paperwork for the exhumation,” recalls Ramón

That same day, at the request of the Abigail’s parents, Police Inspector Elmer Sabillón orders a group of investigators to go the location and begin an investigation.

Thursday July 10, 2014

Fourteen days after she disappeared, five days after they received the call saying that she is dead, three days after the investigators visited Melvin’s abandoned house, Abigail’s body is finally exhumed. She is dressed in an orange blouse, blue jeans, a black bra and blue underwear, the same clothes she wore when she left the house two weeks ago. She’s wearing two metal rings, one green and one gray. Her face is wrapped in a yellow cloth and her body shows signs of torture.

Forensic Medicine takes the body to perform the autopsy. The authorities detect several fractures and assumed that before dying she was a victim of rape, a conclusion that could not be proved due the state of decomposition of the body.

Autopsy Report 1514-2014 performed by forensic specialists indicates that the body is that of Abigail. The body shows three blunt wounds, located on the left region of the neck, the left parietal region of the head and the left forearm along with a flesh wound and a bone fracture. In scientific terms, it means that she was killed by a blow to the head and neck from a hard object – it could have been a stick, a stone, or a pipe. She had the will to live until the end, trying to protect herself with her arm, which was also cruelly shattered by the blows.

Saturday July 12, 2014

Forensic specialists delivered the body to Abigail’s parents, who immediately took it to the public cemetery in Calpules, a neighborhood in San Pedro Sula, to give her a Christian burial. Due to the state of decomposition, she could not have an open-casket funeral in a church as is the usual Christian custom.

“We hoped to find her alive, but she is no longer suffering, she is not being tortured and we have a grave where we can visit her and remember,” exclaims her father Emerson through tears. His heart is broken, his face flooded with drops of water pouring from his eyes on the sunny July afternoon.

Chapter 5: A small blow against impunity

July 12-20, 2014

Meanwhile, Ramón and an investigator from the Public Prosecutor’s Office were working together to find the whereabouts of the criminals. In the process they identified two witnesses were would be instrumental to the resolution of the case. They discovered patterns through photographs and made further inquiries.

One of the witnesses, identified as “M-09” for his/her protection, said that at 12:45 in the afternoon on June 26, 2014, Victor Manuel Pavón, known as “El Pelón” and Luis Gerardo Fuentes, known as “Kevin Pacheco,” took Abigail by force. M-09 also recognized the gang members from the photographs taken by Ramón and the other investigative police agents.

The other witness, known as “2610-2014,” claims to have seen Pacheco and Pelón put the girl in a vehicle that was waiting in the street and take off in the direction of the neighborhood Planeta. Hours later at the Melvin house, the same witness observed various people coming and going, including known criminals in the community, like El Pelón, Kevin Pacheco, El Bote, Samuel and El Aguila.

“I was walking through the street and heard someone shouting inside and there was always someone keeping watch,” said the witness in his statement before the judge, as anticipated evidence.

The investigations moved forward, and in a short time they submitted the case to the Public Prosecutor.

“You are asked to concede to the request for the pretrial detention of Victor Manuel Pavón Prieto, known as El Pelón and Luis Gerardo Hernandez Fuentes, known as Kevin Pacheco, for the crimes of unjust deprivation of freedom, and murder,” – states the report the Investigative Police Department sent on July 20, 2014 to the then-Coordinator of the Prosecutor of Crimes against Life, Marlene Banegas. Just months later Benegas, a dedicated official, would be shot in circumstances which are still unclear but that clearly show the power and audacity of the criminal gangs in Honduras.

On the same day that the Public Prosecutor received the investigative report, a criminal judge in San Pedro Sula ordered the capture of Pacheco and El Pelón. Hours later, in an operation in the Rivera Hernandez area organized for that purpose, agents of the Investigative Police Department with the help of Ramon, captured both suspects. The young men were handcuffed and placed in the patrol car that drove them to First Station on Third Avenue in San Pedro Sula.

Later they were brought before the judge, who after dictating the formal prosecution order, sent them, with pretrial detention, to the cells of the National Penitentiary.

The capture of Victor Manuel Pavon Prieto, known as El Pelón and Luis Gerardo Hernandez Fuentes, known as Kevin

July 23, 2016

Two years later, in a public oral judicial hearing on July 23, a sentencing court declared that El Pelón and Pacheco were responsible for the murder of Abigail Andrea. To prove the guilt of the accused, they presented documentary, circumstantial, expert and scientific evidence. Although the punishment has not been dictated, the Penal code dictates between 20-30 years for homicide.

In a country where barely four out of every one hundred homicides are punished, this counts as a small victory for justice and decency.

Chapter 6: Power Vacuum or Ray of Light?

While finding the body of their daughter, burying her and seeing her assailants captured may have led to a sense of peace and closure for Abigail’s parents, it also forced open a new chapter filled with challenges. After their daughter was exhumed, they received death threats and like hundreds of thousands of countrymen, they fled to the United States.

In a community where Los Ponce operated, many are of the opinion that the downfall of this gang was to have killed Abigail, a view shared by investigator Ramón. Before that crime, he says, Los Ponce committed crimes right and left in total impunity.

“And there (with the death of Abigail) was where the investigations started that now have several of the gang’s members in jail,” –states Ramón- “now some are in prison and others are dead.”

Besides Pelón and Pacheco, Cleaford is also in prison for another murder perpetrated by the gang. Cristian Ponce, the group founder, was killed at the hands of suspected members of the Olanchanos Gang in the beginning of 2013. They say his own brother handed him over and paved the way for the gunmen to enter his home and gun him down. At the time of Abigail’s abduction, he had taken the command of “El Moisa,” but his leadership was not respected. The situation led to betrayal, and the gang members started to kill each other. Moisa was found dead, buried in a vacant lot near the border of the neighborhood of Asentamientos Humanos on July 29, 2014, 24 days after the gang killed Abigail and 34 days after the kidnapping.

According to the Coordinator of the Prosecutor for Crimes against Life in San Pedro Sula, Eduardo Figueroa, the conviction obtained against the Abigail’s murderers caused a ripple effect throughout the city.

“In the first place, it allows for justice for the victim and her family, then it develops trust in the institutions, and ultimately it prevents the criminal from continuing to kill people in the streets of this country,” he tells Revistazo

The prosecutor recognizes that there are significant challenges to achieving more of these sentences, the main challenge being a lack of investigation.

“Investigations are not conducted for various reasons: Institutional factors, availability of agents, the trust factor amongst citizens,” he expressed,“In many cases people refuse to provide information because they do not trust the justice system.”

The Christian organization where Ramon works is helping victims, witnesses and the authorities to overcome these challenges, little by little, at least with regard to a number of crimes committed in the Rivera Hernandez area, managing to nail down serious investigations that led to the capture and conviction of the perpetrators. This organization helps investigate the facts, gives required psychological care to victims and witnesses, and includes a group of lawyers who support the prosecutors throughout the judicial process.

With the support of this organization, the authorities have been able to fully investigate the homicide of Melvin Clavel, the owner of the house where Abigail was assassinated and buried. This house, that for a time was the scene of horrific crimes, is now in the hands of an evangelical pastor, Daniel Pacheco, who organizes several programs for at-risk youth and other community events.

In a recent report written for the New York Times, journalist Sonia Nazario mentions that in the past two years the number of homicides has been reduced by 62 percent in Rivera Hernandez, and now the area is safer for children who once again can go out and play in the streets.

However, the fall of one gang paved the way for another. A reliable source told Revistazo that the void left by Los Ponce in the Sinai, Cerrito Lindo and La Central areas is now being filled by the MS-13, under the command of the gang member known as “El Piojo” (the Louse).

“They have established rules, like do not cause trouble, do not file complaints with the police, do not abuse children and zero gossiping,” he stated. He said that if one of the community members steps out of line, they will call them out; if the person continues to do so, that warning will be followed by “a little heat” or torture. If the disobedience affects one of the gang members or the criminal organization, it can lead to death.

There will be more work for the authorities in Rivera Hernandez. However, there is hope that the captures and sentences that have recently been obtained, like in the case of Abigail’s murderers, will inspire courage within the community not to remain silent but to report the criminals who have kidnapped their communities.

Association for a More Just Society - U.S. (ASJ-US)

PO Box 888631, Grand Rapids, MI 49588

| info@asj-us.org | 1 (800) 897-1135

ASJ (formerly known as AJS) changed our name in 2021 to reflect our partnership with Honduras and our Honduran roots. Learn more.

© 2022 ASJ-US All Rights Reserved. ASJ-US is a U.S. registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Powered by AutomationLinks