One reason so few cases of corruption are punished is the huge backlog the court faces. Over the past seven years, ASJ’s study found, the TSC’s investigations took an average of 6.6 years.Some decisions took as long as ten years, after which the accused would either face an administrative sanction, proceed to a criminal sanction, or see the charge dismissed.

April 5, 2017

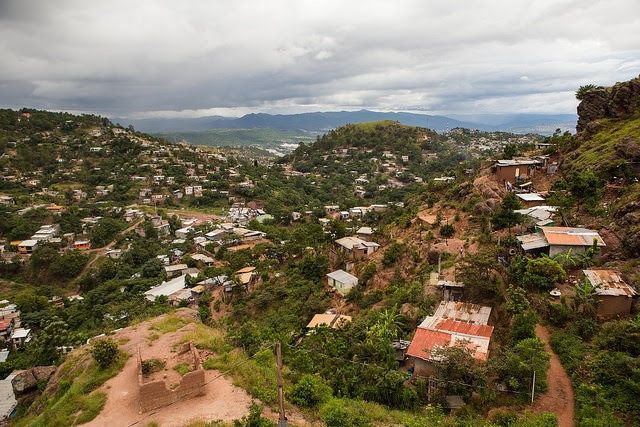

With politicians in the pockets of drug traffickers and hundreds of millions of dollars robbed from government coffers, Honduras has been racked by accusations of grand corruption, illicit enrichment, and organized crime.

But if the Honduran government had been working as it should, none of these scandals would have happened. According to a definitive report into Honduras’ Superior Auditing Court, published by ASJ (formerly known as AJS) this March:

“These corruption scandals and institutional crises could have been prevented, detected and corrected if there were an independent Superior Auditing Court with sufficient budget and the technical-juridical capacity and institutional coverage to comply with its constitutional mandate…”

Though it’s not an institution many, even in Honduras, are familiar with, the Superior Auditing Court is one of the most important tools in the fight against government corruption.

Across the world, Superior Auditing Courts are government institutions that perform internal audits, looking for corruption and inefficiencies within the government and issuing recommendations for change. In the United States, this court is called the “Government Accountability Office”. In Honduras, it is the Tribunal Superior de Cuentas, or TSC. The three magistrates who make up the TSC serve in seven-year terms, and act as the “first link in the fight against corruption”.

Unfortunately, in Honduras, this link can act more like a roadblock. Honduran courts cannot proceed with a case of illicit enrichment until the TSC determines that the incident should be taken to trial. No other judicial body is allowed to perform an independent investigation of the case.

Illicit Enrichment, also called Unjust Enrichment is any instance in which someone misuses their power to make themselves rich at the expense of someone else. It could be direct theft, or indirect abuse of power such as granting your own companies lucrative contracts.

Honduras’ TSC has long come under scrutiny for institutional weakness and lack of response to serious accusations of corruption. ASJ, in turn, has long called on the Honduran government to reform the way the court functions, allowing it to investigate and intercept corruption more swiftly and readily.

ASJ’s report, “Citizen Oversight of the Superior Auditing Court 2009-2016” an in-depth study into the organization and management of the court, is the culmination of these years of advocacy. The report analyzes and evaluates key management indicators for the TSC’s previous term and lays out clear suggestions for improvement. As a new court of magistrates begins their seven-year tenure this year, ASJ hopes that lessons learned from past mistakes will strengthen the institution in the future.

Illicit enrichment is one of the most controversial acts of corruption not just because of its frequent links to organized crime, but also because it is one of the crimes that is least investigated, least often sent to trial, and carries the least punishment, the Citizen Oversight Report noted.

In some cases, the accused were ordered by the TSC to pay a fine to restitute the money they had stolen or mismanaged. However, though the majority of thefts were of quantities of $43,000 and above, the majority of fines were levied in cases of thefts of $2,000 or less.

Besides slow, inefficient processes that tended to ignore the biggest offenders, the study also revealed a limited scope for the court’s investigations. The TSC audited less than 50% of public spending, and their investigations did not reach all municipalities.

Some of the TSC’s institutional weaknesses can be attributed to its limited budget. Unlike most public ministries that dedicate 60-70% of their budget to salaries, the TSC designates well over 90% of its budget just to pay its 649 employees, leaving very little space for operating expenses, technological advances, and other tools. Honduras spends far less on its Superior Auditing Court than other Central American countries – Panama spends 20 times more per capita on investigating government corruption.

“We hope that the findings, results, and recommendations that are presented in this report will not only be a challenge for the new court, but also a contribution” said Lester Ramirez, ASJ’s director of investigations and the author of the report, “We hope it orients them to focus their efforts and resources in impactful actions that will help to construct social legitimacy and institutional credibility.”

Association for a More Just Society - U.S. (ASJ-US)

PO Box 888631, Grand Rapids, MI 49588

| info@asj-us.org | 1 (800) 897-1135

ASJ (formerly known as AJS) changed our name in 2021 to reflect our partnership with Honduras and our Honduran roots. Learn more.

© 2022 ASJ-US All Rights Reserved. ASJ-US is a U.S. registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Powered by AutomationLinks